There may be no more contentious issue in nutrition than the topic of dietary fat. Part of the problem is that the word “fat” has many different meanings and connotations:

- an essential macronutrient;

- a type (several types, actually) of bodily tissue; or

- an adjective that many people find insulting or offensive which describes a body shape.

This maze of meaning distorts the scientific discussion of dietary fat — the nutrient we’re going to look at here. The history of nutritional science, including recently discovered frauds and cover-ups, has polarized the debate to the point where it becomes difficult to know the truth.

So before we can sift through the science and share what’s known and generally accepted as our current state of knowledge about fats, we have to examine and untangle some of that history, so we can understand why it can feel so divisive to “chew the fat” about the health realities of good vs bad fat.

A Short History of Dietary Fat

For most of human history, we ate whatever we could get our hands on. Food was often scarce, and its supply unreliable, so we didn’t worry about the possible effects of excess. The problem was typically finding enough food to survive.

As gatherer-hunters, humans subsisted on vegetation and viewed hunting as a high-risk/high-reward activity that could provide an occasional bonanza of calories and nutrients. When the clan brought down a large herbivore like a bison, elk, or impala, every calorie was meted out to various members.

Only with the advent of agriculture and mechanized animal husbandry did the issue of too many calories become an issue. There were two major concerns that then arose: first, a new obsession with how much a person should weigh; and second, questions about whether excess weight contributed to negative health outcomes.

The Fat and Weight Association

It’s hard for us to imagine, but it’s only been about 100 years since most people have known their weight. The first personal scales were fairground curiosities — you dropped in a penny and got a slip of paper with your weight written on it. Soon the scales themselves became loaded games of chance — guess your own weight correctly and get your penny back.

People quickly became fascinated with this new way of assessing themselves. By the late 1920s, Americans became obsessed with whether they were gaining or losing weight. The wife of the Weight-o-Health weighing machine distributor was able to buy herself a brand new Nash automobile with 30,000 fairground pennies, according to a 1928 story in The Los Angeles Times. And people were no longer satisfied with sporadic weighings at carnivals. Once a 1917 patent for a “bathroom scale” made them available for home use, the new industry quickly grew to $80 million in sales per year.

Life insurance companies created weight and height tables that showed “normal” distributions. The new precision afforded by scales and the ability to compare oneself to a so-called “healthy average” led people, especially women, to pay attention to their weight — and their eating habits — on a daily basis.

Being slim went from a possible symptom of malnutrition to a sign of virtue. The fashion industry started making women’s clothing such that bodies had to be adapted to fit into them instead of vice versa. Once narrow hips were “in,” rubber girdles replaced hourglass corsets.

Now calories were to be more feared than coveted. Fasting and dieting became fashionable. And one of the principles of eating for thinness was to reduce or eliminate fats from the diet since, by weight, fat has more than double the calories of carbohydrates and protein. And once “fat” became a bad word for the human body, it was quickly apparent that “fat,” the macronutrient, had a serious branding problem.

Attacks on Fat

Body shape wasn’t the only factor causing Americans to become wary of fat in their food. Studies dating from the late 1940s showed a correlation between high-fat diets and high blood cholesterol, which itself had been associated with cardiovascular disease. Patients deemed high-risk for heart attacks and strokes were urged to adopt low-fat diets.

By the 1960s, the medical mainstream and popular media started touting low-fat diets as appropriate for everyone, not just high-risk heart patients.

And in the 1980s, the low-fat approach became a societal craze of sorts, and was promoted by everyone from doctors to the government and, of course, the food industry itself. Processed food manufacturers began slapping “low-fat” on their packaging while filling their products with added sugars.

The sugar industry took advantage of the situation by paying Harvard researchers to skew their findings in favor of sugar by blaming fat for all sorts of health problems.

These days, you can’t turn around without confronting a skirmish in the “diet war” between fat and carbohydrates. The anti-fat proponents tell us that high consumption of fat causes obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and possibly cancer.

But the “fat is back” advocates point to the meteoric rise in overweight and obesity during precisely those decades when low-fat diets were the rage. They highlight studies that appear to show that replacing fat with sugar leads to even worse health outcomes.

There are even some epidemiological studies that concluded that fat, and saturated fat from animal sources, in particular, doesn’t increase the risk of heart disease. By 2014, both Time magazine and The New York Times were telling us that “butter is back.”

So what’s the truth here? What’s the actual scientific evidence about dietary fat? What are the different types of fat? Which ones are good for you? And how much fat do you really need in your diet?

What Is the Function of Fat?

Fat, along with carbohydrates and protein, is one of three critical macronutrients in the human diet. In addition to being a concentrated source of calories, fat provides essential fatty acids. The body cannot make these kinds of fat, so it’s necessary to get them from food. (That’s why they’re called “essential.”)

Fat serves multiple functions in your body. It is the principal way you store energy for later use. It insulates and protects your organs, and works to keep you warm in cold environments. And fat transports and facilitates the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, including A, D, E, and K.

Fat also helps food taste good, which makes sense given its importance for human biochemistry. And since it’s a concentrated source of calories, it also makes sense that eating fat contributes to satiety.

Speaking of calories, your body does a neat trick, one primed by eons of evolutionary pressure. All excess calories that your body doesn’t excrete, and that are not used by your body’s cells or turned into energy, are converted into body fat.

Triglycerides

Fat exists in animals and plants in a variety of forms. The most common fat form, in your food and in your body, is called “triglycerides.” The name refers to three fatty acids attached to glycerol, a form of the simple sugar glucose. Triglycerides are crucial to your survival, serving as your main source of long-lasting energy. And you don’t just need to rely on food to supply them — your liver can manufacture triglycerides when needed.

When you eat extra calories, your liver increases its production of triglycerides, which is kind of like your body’s way of saving them for a rainy day.

The trouble is that excess triglycerides in your bloodstream are not a good thing, especially in combination with high LDL (bad) cholesterol. High triglyceride levels are linked with fatty buildup within artery walls, which increases the risk of heart attack and stroke.

Types of Fat

There are, broadly speaking, three categories of fat — saturated fat, unsaturated fat, and trans fat.

Saturated Fat

You can identify saturated fat by the fact that it’s generally solid at room temperature (unless you live in a sauna).

Saturated fat is found mainly in animal products like red meat, cheese, chicken, and eggs. There are also some plant foods high in saturated fat, including coconut and coconut oil, palm and palm kernel oil, and chocolate. (For the chocolate lovers of the world, I hasten to add that the saturated fat in cocoa butter, stearic acid, gets converted by your liver into a much healthier unsaturated fat.)

Unsaturated Fat

Unsaturated fat comes in two main varieties, polyunsaturated and monounsaturated. The term “polyunsaturated” refers to the chemical structure having at least two double bonds, and, as far as I can tell, has nothing to do with parrots.

Polyunsaturated fat comes in two main types, omega-3 and omega-6, depending on the position of the first double bond. People get polyunsaturated fats mainly from plant foods such as seeds and nuts; seed, nut, and vegetable oils; avocados; and certain forms of algae. For many people, fish are also a major source of the long-chain omega-3 fats DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) and EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid).

Usually, oils with polyunsaturated fat remain liquid at room temperature, but they will turn solid if they get cold enough.

Monounsaturated fats, such as the lesser-known omega-9s, are primarily found in plant foods like nuts, seeds, avocados, olives, and peanuts (plants typically contain more than one type of fat). Like their polyunsaturated friends, they are liquid at room temperature and turn solid when the temperature gets nippy. They are especially high in olive, almond, and avocado oils.

Trans Fat

While trans fat can occur naturally, most of the trans fat in the modern diet has been created artificially through a process called hydrogenation. This process — in which liquid vegetable oils are heated in the presence of hydrogen gas and a catalyst — makes the oils shelf-stable and also stabilizes their flavors.

This stability made trans fats an extremely lucrative ingredient in the industrial food supply, as items made with trans fat didn’t need to be refrigerated — or rushed from production onto supermarket shelves. As a result, consumers enjoyed the convenience of trans fats through the use of margarine and shortening, which could withstand repeated heating without breaking down. Thus, the modern food system became saturated (here, a nonchemical term) with trans fats in fast food, commercial baked goods, and processed foods.

The only problem is that trans fat is really bad for your health. So bad, in fact, that in 2015 the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) deemed artificial trans fats “unsafe to eat” and gave food manufacturers three years to eliminate them from all products. The World Health Organization followed suit, launching a global initiative named REPLACE, with the goal of making the global food supply free of artificial trans fats by the end of 2023.

The Trans Fat Loophole

Don’t breathe a full sigh of relief yet, however. In the US, the FDA has allowed trans fats to remain in the commercial food supply through a loophole — if the product contains less than half a gram of trans fat per serving, the manufacturer can “round down” to zero. The easiest way to pull off this trick is to decrease the serving size.

According to the Mayo Clinic (the clinic’s name, Mayo, is trans-fat-free, although the food isn’t), foods that commonly contain trans fats in “under the radar” amounts include commercial baked goods (cakes, pies, and cookies), microwave popcorn, frozen pizza, fried foods, nondairy creamer, and stick margarine, among others. Since mathematical shenanigans will hide trans fat from the nutrition facts label, you’ll need to scour the ingredients list for the word “hydrogenated.”

For example, Crisco, the best-known brand of shortening, pulls the “round down to zero” trick in its nutrition label, claiming to contain “0g of Trans Fat per serving,” despite the fact that its second ingredient is fully hydrogenated palm oil.

If you include any meat or dairy in your diet, you will also be exposed to some naturally occurring trans fats, which may be just as damaging to your health as the artificially created ones.

How Much Fat Per Day Is Optimal?

So how much fat should you eat? According to the USDA, the acceptable macronutrient distribution range (AMDR, which is not to be confused with ASMR YouTube channels of people whispering, turning pages, or repeatedly sticking their hands in jello) is around 20–35% of calories.

The type matters, as well. The USDA recommends that 15–20% of your calories come from monounsaturated fats, 5–10% from polyunsaturated fats, less than 10% from saturated fats, and none from trans fats. Additionally, they advise eating less than 300 mg of cholesterol per day.

Omega-3 fatty acids have their own recommended daily allowance, which, due to lack of evidence, is called “intake adequacy” rather than an official Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA). The number varies by age, sex, and pregnancy or lactation status, but is in the range of 1–2 grams per day, for all categories.

A note about that “less than 10% from saturated fats” recommendation — individuals two years and older can make enough of their own saturated fats not to need any from their diets, so “zero” is a perfectly appropriate recommendation in most cases. Also, a reminder about trans fats: There is no need for your body to consume any trans fats.

A Plant Perfect Low-Fat Diet

Renowned cardiologist and Food Revolution Summit speaker Caldwell Esselstyn Jr, MD, encourages his cardiac patients to limit fat to 15% of calories, and in severe cases, to no more than 10%. This diet, which he named “Plant Perfect” and introduced in his book How to Prevent and Reverse Heart Disease, is based on whole plant foods, with no added oil, and no nuts, but with adequate omega-3 fats from green leafy vegetables, flax meal, and chia seeds.

Dr. Esselstyn tested the diet on patients with advanced cardiovascular disease, including many who had been told by their physicians to “put their affairs in order” because there was literally nothing else the healthcare system could do for them. But as Dr. Esselstyn tells us in this study, on his extremely low-fat diet, “patients become virtually heart-attack proof.”

One study that began in 1985 with about 20 of these “death’s door” patients achieved such dramatic results that some of the participants were interviewed about their experiences in the 2011 documentary Forks Over Knives, and many are still alive and well today.

Further support for the efficacy of a low-fat or very low-fat diet comes from data from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study, which concluded that 15% of calories from fat was the upper limit for those who wanted to prevent breast cancer recurrence.

So it looks like a very low-fat diet may be best for the reversal of heart disease, and for preventing recurrence of certain forms of cancer. But that doesn’t mean that all fats are bad and should be avoided — nor that a very low-fat diet is optimal for all other situations or conditions.

Debunking Myths About Fat

There are a couple of myths about fat that lead people to make questionable food choices. One such myth vilifies all fat as something to be avoided. The second myth conflates eating fat with being fat, and blames fat consumption for the accretion of fat on the body when the truth turns out to be a good bit more nuanced.

Myth 1: All Fat Is Bad

As we’ve seen, dietary fat is essential for survival and health. So viewing all fat as the same — bad — can set a person up for deficiencies in certain key nutrients. And if you’re eating less fat, then you’re eating more of something else. If that something else is refined white flour and sugar, that’s hardly an improvement, and may actually harm you more than a higher-fat diet. (Although practically speaking, diets high in saturated and trans fats also tend to contain lots of processed and artificial foods as well, so it typically doesn’t operate as a zero-sum game.)

Omega Fatty Acids

Since your body can’t manufacture its own omega-3 and omega-6 essential fatty acids, you have to get them from food. And while you need both, the ratio between them is important. Not enough omega-3 fatty acids compared with omega-6s can contribute to inflammation in the body. An ideal ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 appears to be somewhere between 4:1 and 1:1, a range associated with better heart and brain health, less inflammation, reduced risk of cancer, and even higher IQ scores.

The modern industrialized diet doesn’t come close to this ratio, unfortunately. Some sources estimate that the average American consumes at least 14 times more omega-6 than omega-3 fatty acids. If you’re looking to reduce omega-6s (which most of us need to), reduce or eliminate the consumption of processed foods containing sunflower oil, corn oil, safflower oil, and cottonseed oil.

There are three main types of omega-3 fats — EPA, DHA, and ALA. Your body needs EPA and DHA, which are “long chain” versions. The good news is your body can synthesize these compounds from ALA, which you can get in abundance from flax and chia seeds (as well as lesser amounts from walnuts, hemp seeds, and canola oil).

Unfortunately, not all bodies convert ALA into EPA and DHA efficiently, so you could be deficient in the latter two if you don’t eat fish or take an algae-derived supplement. After all, the EPA and DHA that fish have in their tissue comes from algae in the first place. (For more on the health, ethical, and environmental impacts of fish, see our article here.)

That’s why many vegan health experts recommend taking an algae-based EPA/DHA supplement. (My personal favorite comes from Complement, and also incorporates other critical nutrients that can be hard to source on an exclusively plant-based diet. You can find out more here. And if you make a purchase from that link, a contribution will also be made to FRN’s work. Thank you!)

Saturated Fat

When we look at the available scientific evidence, it’s pretty clear that, in general, the less saturated fat you eat, the lower your risk of chronic disease and the better your overall health.

A single high-fat meal — particularly one high in saturated fat — can cause inflammation directly after eating. Of course, one meal isn’t going to make a huge difference to most people, but repeating any bodily injury multiple times a day for years and decades can greatly increase the risk of a multitude of diseases and disorders.

Saturated Fat and Heart Disease

Studies have found that replacing saturated fat with unsaturated fat, particularly polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fat, reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease (the world’s #1 killer by a wide margin). And long-term trials suggest that reducing dietary saturated fat lowers the risk of combined cardiovascular events by 21%.

Saturated Fat and Alzheimer’s

Your heart isn’t the only organ negatively affected by saturated fats. Cutting back on meat and dairy can also benefit your brain. A study from 2003 found that people who consumed the least saturated fat had less than half the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease compared to those who consumed the most. Those results held even when accounting for the presence of the APOE4 gene, which predisposes its carrier for Alzheimer’s.

Other studies have replicated this finding, with most showing that total fat consumption wasn’t a risk factor, but that saturated fat consumption was. (In fact, polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats have been associated with a decreased risk of Alzheimer’s — although whether that’s because they were replacing saturated fat in the diet is unclear.)

Saturated Fat and MS

The inflammation generated by saturated fat can even trigger the onset of multiple sclerosis, as well as hasten and intensify its progression. This can happen via several mechanisms, including (warning: very technical language ahead!) degeneration of neurons and glia (the cells of the nervous system that support the neurons and facilitate the transfer of electrical impulses and information); oxidative stress damaging the myelin sheaths that protect and insulate the nerves, injuring the energy-producing mitochondria in the brain; and hypersensitizing the immune system so that it starts attacking your body.

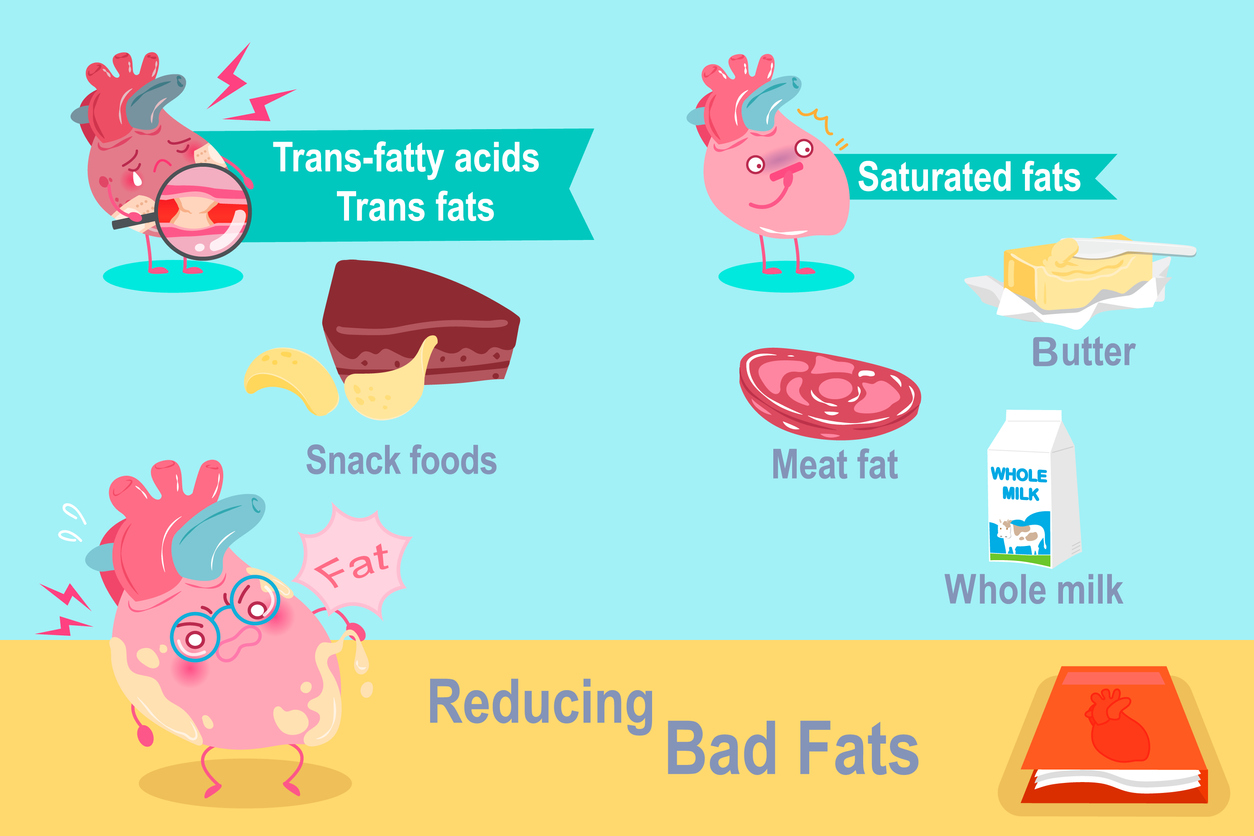

Trans Fats

Trans fats are a rare case where nutritional absolutism is called for — they’re always bad for you. Lots of evidence points to trans fats being associated with risk factors for cardiovascular and other chronic diseases. They raise bad LDL and lower good HDL cholesterol. They trigger inflammation. And they contribute to insulin resistance, which is a key cause of metabolic syndrome and the root cause of type 2 diabetes.

And if that isn’t enough to put you off eating Crisco by the tablespoon, trans fats have also been associated with breast cancer, a shortened pregnancy, risks of preeclampsia, disorders of the nervous system and vision in infants, colon cancer, obesity, and allergies.

Myth 2: Fat Alone Can Make You Fat

I get it, there’s fat in food and fat (adipose) cells in your body. It’s an easy mistake to make that the only way to get fat is by eating fat.

Now, it’s true that excess fat consumption can contribute to overweight and obesity. That’s because dietary fat contains nine calories per gram, compared to just four calories per gram of carbohydrates and protein. One way to gain weight is by favoring calorically dense foods that are high in fats. Shelled walnuts, for example, provide 654 calories per cup. By contrast, a cup of fresh cantaloupe contains just 60 calories. This means you could eat ten cups of cantaloupe before consuming as many calories as are in that single cup of walnuts.

So if you’re trying to lose weight or not gain weight, you should be aware of the amount of calories you’re eating. And there’s no more dense source of calories than fat. But most people don’t gain weight because they’re eating too much healthy fat in a vacuum. You have to look at the whole diet and at the overall ratio of caloric consumption to what a body needs.

Some studies indicate that people self-limit the amount of fat they consume naturally because high-fat foods can trigger satiety. The problem for most people is eating too much fat coupled with sugars and other processed carbohydrates. There’s evidence that the sugar/fat combo actually releases endocannabinoids that promote hunger and the storage of any extra calories as fat.

The processed food industry often combines the least healthy saturated and trans fats with highly palatable refined grains, sugar, and excess sodium, creating a powerful cocktail of appetite enhancement and subsequent weight gain. Sugar itself will get converted to fat when eaten in excess. The amount of simple sugars most people consume in a typical modern diet is itself a significant contributor to our current obesity epidemic.

So What Fats Should You Avoid?

To recap — based on the data we have available today, it seems wise to limit saturated fats, which mostly come from meat and dairy but can also be found in tropical oils such as coconut and palm. Any dishes that use these ingredients in significant amounts will also tend to be high in saturated fat. When shopping, make sure to read the ingredient lists of foods.

For most people, the easiest way to avoid saturated fats is to move towards a plant-based diet. If you’re new to a plant-based diet, and want some help getting started, this article could help.

You can (and should) avoid trans fats by staying away from fast food, animal products, and hydrogenated and partially hydrogenated vegetable oils.

Partially hydrogenated soybean and vegetable oils are commonly used for frying and cooking fast foods and processed foods. You can avoid them by making your own baked or air-fried plant-based versions of burgers, french fries, onion rings, and fried “chicken” at home.

You can avoid the trans fats that come in salad dressings sold in supermarkets and served at fast food restaurants by making your own. Some of the yummiest and healthiest salad dressings can actually be made from high-fat whole food ingredients like nuts and seeds instead of oils.

Cakes, cookies, and other commercial baked goods are also often made with trans fats. Check out our detailed guide on healthy plant-based cooking and baking substitutes, so you can make your own healthier versions at home.

Another common place to find trans fats is in frozen foods. I know they can be convenient, but so can making time for batch cooking. And that way, your convenient “heat and eat” meals can support your health as well as play well with your busy schedule. Here’s our comprehensive guide to prepping plant-based meals.

You can also find trans fats in some brands of microwavable popcorn, as well as potato and corn chips. This article shares healthy ways to satisfy your craving for a crunchy snack.

Fats to Eat

Instead of saturated and trans fats, opt for foods containing unsaturated fats. Both mono- and polyunsaturated fats can provide health benefits, when consumed in moderation and in proper ratios. They’re found in plants, such as nuts and seeds, and nut and seed butters (including walnuts, cashews, and peanuts; and hemp, chia, flax, sunflower, and pumpkin seeds).

And remember that whole foods, being far more than the sum of their nutrition labels, can provide not just fats but also many essential micronutrients as well. So while avocado and olive oils can be a small part of a healthy diet, you might want to eat avocados and olives themselves, rather than just consuming the oils extracted from these foods.

Recipes with Healthy Fats

You can eat these foods on their own or include them as ingredients in a variety of dishes. Here are three examples of recipes that showcase healthy fats in a snack, salad, and main course. Whole food, plant-based fats are nothing to fear with these nutritionally-rich, mouthwatering recipes!

1. Sesame Sunflower Chia Bites

These nutritious bites have so much to love, including multiple forms of healthy fats in sesame, chia, and sunflower seeds. Sesame and sunflower seeds are great sources of polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fat, while chia seeds provide plant-based omega-3 fatty acids. What makes these bites even more satisfying is the nutty flavor of sesame and sunflower seeds combined with the natural sweetness of the dates. With their healthy fats in tow, these seeds are also a good source of protein and fiber to help keep you energized and satisfied.

2. Simple Kale, Avocado, and Pumpkin Seed Salad

When it comes to plant-based healthy fat champions, avocados and pumpkin seeds reign supreme. These wholesome ingredients are rich sources of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats that lend themselves to the velvety and crunchy textures in this Simple Kale, Avocado, and Pumpkin Seed Salad. Plus, this superfood salad is teeming with fiber and loads of nutrients such as vitamins K1, C, E, and B6, as well as plant-based protein thanks to the pumpkin seeds.

3. Creamy Asparagus Risotto

The beauty of healthy fat (aside from its nutrient benefits) is its ability to elevate and transform even the simplest of plant-based dishes into an elegant culinary affair. Cashews get some of the credit here — they’re blended into a silky, creamy, umami cheese sauce, and then simmered together with asparagus, spinach, and brown rice. This dish is packed with healthy fats, loads of fiber, and nutrients galore. Sounds too good to be true? We’re here to let you know that plants are magical like that!

The Type of Fat Matters!

A persistent health message over the past 50 years has been to avoid all sources of fat, leading both to an irrational fear of eating any fat, as well as the extreme opposite position that the more fat, the better. Once we get past the hype and look at the science, however, it becomes clear that some types of fat, in appropriate amounts and ratios, are necessary for health. The type of fat — and its source — matters. While saturated fats and trans fats can harm us, whole food, plant-based sources of fat, such as avocados, nuts, and seeds, can play an important role in a well-balanced and varied diet.

Tell us in the comments:

- Have you ever been on a very low-fat or very high-fat diet? What was your experience?

- What are your favorite sources of healthy, plant-based fat?

- What’s your favorite recipe that includes nuts or seeds?

Featured Image: iStock.com/morisfoto